The Netherlands adds ‘slow-motion bank wrecks’ to list of things it’s known for, right after ‘clogs’ and ‘windmills’

Repost from FT Alphaville

Raise your hand if you didn’t first hear about the way in which the Dutch government took over ailing SNS Reaal on February 1st and think ‘oh, really now?’ along with an arched eyebrow.

The mechanics of the takeover are interesting indeed, but given that two of the four largest Dutch banks have been nationalised, we have a bigger picture question:

How much warning was there that SNS Reaal was on the brink?

Surely there would have been some worrying results in the European Banking Authority’s Capital Exercise from last autumn.

Umm, no, actually. (Probably saw that coming, didn’t you?)

SNS Bank reported 13.0 per cent Tier 1 capital as a percentage of risk-weighted assets as of June 2012. For comparison, ING had 13.4 per cent, Rabobank 16.9 per cent, and government-owned ABN Amro 12.5 per cent.

To back up a step, SNS was on the receiving end of €750m of aid in 2008. It hadn’t paid that back, so the government was still rather involved with the group, or at least one would hope so. As the Finance Minister Dijsselbloem outlined in the announcement of the nationalisation, the Dutch central bank (DNB) totally insisted on the formulation of plans. Like, for reals.

Plans are important, particularly when a bank has an underperforming real estate portfolio of some €8.55bn (without provisions) that constitutes a large amount of its total assets (€82.3bn balance sheet). And also it happens to be the fourth largest bank, third largest life insurer, and fifth largest non-life insurance company in the country while having 6,700 employees.

Right, the plan! We were talking about the plan! From 2008 (quoting from the finance minister’s letter on the nationalisation, emphasis ours):

DNB [the Dutch Central Bank] – in order to speed up the phasing-out effort initiated by SNS Bank – requested the firm to draw up exit plans for the international real estate portfolio showing how, when and at what loss this portfolio could be phased out.

Then there was some finger tapping. Then things got more serious:

In mid-2011, DNB repeated its request, this time regarding the phasing-out of the entire real estate portfolio. In 2011, DNB also asked SNS REAAL to formulate an action plan regarding the planned repayment of the government aid and the vulnerabilities identified.

Ja, doe maar! Get on with it already.

When this proved inadequate, DNB requested an additional action plan.

And then finally…

In December 2011, when it became plausible that the problems could not be fully resolved through private means, DNB and the Ministry of Finance set up a joint project group to analyse the possible scenarios and options (private, private-public and public) with regard to SNS REAAL and to set up an emergency safety net should the problems escalate and acute intervention would be required.

***SPOILER ALERT***

The project group failed when talks with banks and then also a private equity fund came to nothing. Those had been going on for quite some time, and once it was clear that an all-private solution wasn’t going to be forthcoming, the government had switched to a strategy of exploring a public-private solution (details of which in the letter).

No joy though. It all came to a head when a deadline given to SNS by the central bank — on January 27th, which is plenty of time when closely monitoring a bank when one lives on a different planet maybe — was missed:

The continuing problems at SNS Property Finance forced DNB to conclude that SNS Bank required twice as much core capital as was available, the capital deficit. DNB had imposed a deadline of 31 January, 18:00 hrs, on SNS Bank to come up with a solution to remedy the funding deficit.

If the government hadn’t stepped in, a bankruptcy was considered inevitable, and they didn’t want to take the risk of causing financial instability by allowing SNS to go under.

Had SNS entered insolvency proceedings, it would have triggered the Netherlands’ Deposit Guarantee Scheme and the costs to that would have to be met by other banks, which the government feared would be too high a burden for them, causing downgrades, increased funding costs, and so on — all of which would ultimately increase the potential burden on the Dutch taxpayer.

Furthermore:

Moreover, recourse to the DGS would imply that over 1 million account holders would temporarily be prevented from using their payment accounts, which might put them in financial difficulty, possibly causing social unrest.

Hup Holland.

But why did it prove impossible to find a solution for SNS that didn’t involve full-up nationalisation? As the finance minister outlined, selling the better bits of the SNS Reaal group wasn’t as feasible as one would perhaps think:

…partly attributable to two problems: a) the double leverage and b) unit-linked insurance policies. Due to these two problems, the separate parts of SNS REAAL would not yield sufficient proceeds to strengthen SNS Bank’s or REAAL’s financial position. As a consequence of the double leverage, a part of the proceeds of the sale would have to be used to pay off loans entered into by the Holding.

That is, the property portfolio was causing the damage to the capital position as it deteriorated, but the double-leverage and unit-linked insurance issues made it impossible to raise money to plug said hole.

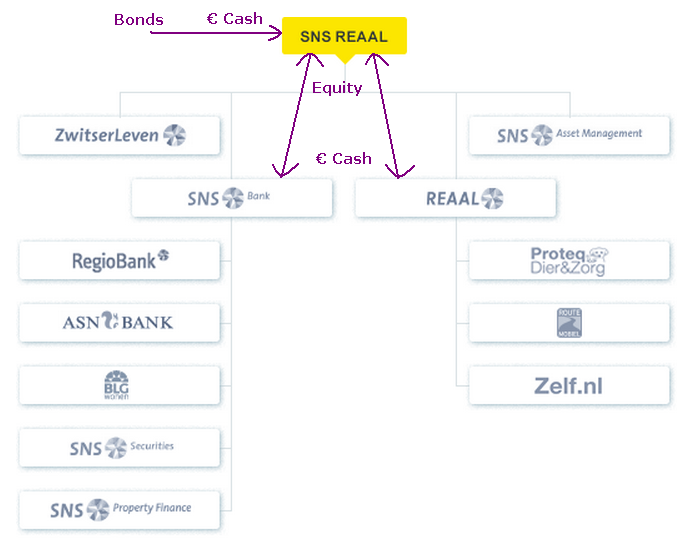

To explain “double-leverage” we’ll need a picture:

It’s where the holding company — SNS Reaal in the above — borrows money, and then uses it to buy equity in its subsidiaries, among them SNS Bank and also the insurance subsidiary Reaal. Total double leverage at the end of 2012 for the group was €909m. The consequence of this:

This means that if parts of the insurer are sold off, for instance, not all of the released funds may be used to solve the bank’s problems, because a part has to be used to redeem loans taken out by the holding.

Potverdorie! Shucks.

It’s not unique to SNS either, as per footnote six:

6 Such double leverage structures are often found in bank-insurance conglomerates. The underlying idea is that banks and insurers have strongly different risk profiles, so that pooling and sharing of risks at the holding level can reduce the overall risk level of the bank/insurer conglomerate. However, if both the bank and the insurer run into problems, as in 2008, when hard times hit both banks and insurers, the holding will a double problem to contend with. Since the 2008 crisis, therefore, supervisors and investors have looked askance at double leverage, which they regard as risky and like to see phased out.

As for unit-linked insurance policies, these insured investment products turned out to be overpriced, and banks are having to pay compensation to holders. It’s still uncertain what the final bill will be.

SNS was an accident waiting to happen. If anything, it’s a wonder it took that long.

But let’s finish on a high (foot)note, shall we?

5 According to the latest Overview of Financial Stability published by DNB (autumn 2012), the entire Dutch banking industry holds some €80 billion in domestic commercial real estate exposures. It also holds some €20 billion’s worth of foreign exposures. On a balance sheet total of about €2,200 billion, this adds up to an average exposure of some 4.5% of total assets for the Dutch banking sector. For the other systemic banks, the exposure is, in fact, slightly lower owing to the large size of SNS’s position.

Related links:

Dutch-bottomed bank bondholders – FT Alphaville

Netherlands rescues SNS in €3.7bn bailout - FT

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/2013/02/11/1380672/the-netherlands-adds-slow-motion-bank-wrecks-to-list-of-things-its-known-for-right-after-clogs-and-windmills/?